1 / 15

First staged in 1975, No Man's Land is the latest of Harold Pinter's plays to be revived in the West End. The production stars Michael Gambon as the boozy Hirst, who finds himself playing host to a stranger named Spooner (played by David Bradley). The Duke of York's production also stars Little Britain's David Walliams and is directed by Rupert Goold

- Gallery (15 pictures): As No Man's Land wins rave reviews at the Duke of York's theatre in London, pause for thought and find out how much you know about Harold Pinter and recent productions of his plays

No Man's Land

Duke of York's, London

-

- The Guardian,

- Wednesday October 8 2008

- Article history

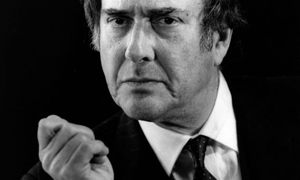

A touch of gothic ... Michael Gambon, David Bradley and Nick Dunning in No Man's Land. Photograph: Tristram Kenton

Every production of Harold Pinter's tantalising, poetic play yields new meanings. And Rupert Goold's eagerly awaited revival, originating at the Gate theatre, Dublin, ushers us into the strange, spectral world that characterised his productions of Shakespeare and Pirandello. In Goold's hands it becomes a play about a man who steps off the Hampstead streets into a living limbo.

- No Man's Land

- by Harold Pinter

- Duke of York's,

- London

- WC2N 4BG

- Until Jan 3 2009

- Box office:

0870-060 6623

At first, all seems familiar. David Bradley's lank Spooner, minor versifier and potman, is invited into the luxurious home of Michael Gambon's blazered Hirst. Increasingly we get a sense of dislocation. In Giles Cadle's sombre set, a staggeringly well-equipped bar looms large. Gambon's startling Hirst seems semi-paralysed by drink, as if his knees could hardly support his massive torso. When Hirst's servants, Briggs and Foster, arrive they resemble a pair of sadistic thugs exuding an air of heavy menace.

If there is a touch of gothic to Goold's production, it serves its purpose. Its aim, I deduce, is to suggest Spooner has unwittingly entered a halfway house between life and death. Hirst, a litterateur haunted by dreams and memories, is, as he tells Spooner, "in the last lap of a race I had long forgotten to run". But, while his servants conspire to lead Hirst to oblivion, Spooner attempts a chivalric rescue-act, dragging him towards the light of the living. The assumption is that his bid fails, as all four characters are finally marooned in a no-man's land "which remains forever, icy and silent". The danger in this metaphysical approach is that it might diminish the play's comedy or Pinter's sense of the concrete; but that is to reckon without actors as vibrant as these. Gambon's magnificent Hirst seems to exist in two dimensions at once, and the great morning-after scene where he greets the bedraggled Spooner as if some long-lost Oxford chum is superb. Gambon actually skips across the stage like a dancing porpoise and greets Spooner's charges of sexual misconduct with thunderous disdain. And it is precisely because Gambon radiates a sense of imagined life that his final decline into stony immobility becomes so moving.

Bradley's Spooner also memorably combines a predatory poverty with a touching gallantry. When Spooner praises Hirst for an imaginative leap, Bradley places a gentle hand on his shoulder announcing "And that's why God loves him." In Bradley's hands, it becomes one of the most compassionate lines Pinter has ever written. I was less impressed with David Walliams's Foster, which strangely misses the Orton-esque sexual banditry implied by a description of the character as "a vagabond cock".

This is a compelling revival much aided by Neil Austin's lighting and Adam Cork's subliminal sound. And when audience and cast finally joined in applauding Pinter, seated in a box, I felt it was in recognition of an eerily disturbing play that transports us into a world somewhere between reality and dream.

No comments:

Post a Comment