Playwrights take career breaks for all sorts of reasons, but none quite so strikingly as Václav Havel, the former President of the Czech Republic. This week his first play for nearly 20 years receives its British premiere, at the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. He was, of course, getting on with other things in the meantime, such as seeing the Soviets out of his country, dissolving the Warsaw Pact, reshaping Europe. It was hardly a retreat from drama.

He doesn't much like it when his story is told as if it were a piece of theatre in its own right, for fear that it trivialises that time of mighty shifts in the world order. Yet when you look at this extraordinary life it is hard to ignore completely the parallels between his progress and the sometimes absurdist tone of his work.

Here was an accidental president if ever there was one. On the eve of the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he was a dissident, much-banned dramatist, a few weeks out of prison. He had served several spells, the longest being four years. He had always argued that politics held no interest for him, yet there he was, in the autumn of that year, the leader of the Civic Forum, which was in effect the opposition.

They held their meetings at the Magic Lantern Theatre in Prague, and this is where he was, sitting on the stage, when an aide rushed in to announce that the Government had collapsed beneath the weight of public protest. Out went Gustav Husak, the President who had collaborated with the Soviet invasion 21 years before; within no time, Havel, his successor, was taking up residence in the ancient, daunting castle at the heart of the city.

His trousers were too short, the result of shoddy work by the prison tailor. He was so alarmed by the length of the corridors in the castle that he used a scooter to cut journey times. He remained in office for 13 years, during which time his country split with Slovakia - against his wishes - joined Nato and negotiated for European Union membership. It joined in 2004, the year after he left office.

His new play is called Leaving and tells of one Dr Vilem Rieger, the former Chancellor of an unspecified nation. He's moving out of the official residence. There's the ticklish business of what is his and what is the state's. The press is nosing about. His companion Irena is fretting. There's the question of whether they can billet themselves on a daughter. Think of The Cherry Orchard and King Lear.

But think also of autobiography, particularly when you learn that Rieger's successor intends to turn the place into an erotic multiplex, with everything from petrol stations to brothels. This successor's name is Vlastic Klein, not dissimilar to Vaclav Klaus, the present Czech President, whom Havel is said to despise for his too ready embrace of capitalism. It smacks of payback time, or at least playback time, for the 71-year-old dramatist who spent all those years in exile from his vocation.

Not quite. His explanation is both more mundane and more comic. “I wrote the first manuscript of the play in 1988 and 1989,” he says, “before the revolution. Afterwards I put it to one side. I thought it was passé, and that it [the manuscript] didn't exist any more. But after I had left office I found that my secretary had kept it somewhere, and she gave it back to me.”

So it was not his own leaving of office that inspired the play, he says, but another exodus - the one taking place in 1968, after the short-lived Prague Spring. “After the Soviet occupation many of the reform Communists, starting from the general secretaries and going down to the local party members, were expelled from the party and forced into workers' jobs, and their positions were taken over by collaborators and supporters of the new regime. This disintegration of the court, with everybody who holds high office having some sort of court around himself... when that started to disintegrate, then for some people, when all of a sudden they had to wash windows or something like that, the whole world began to fall apart.”

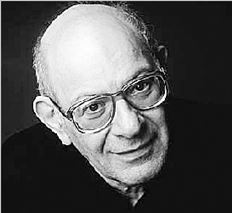

He is speaking in his office in Vorsilska Street, a stone's throw from where the great demonstrations passed in the days before his elevation to the castle. He looks in reasonable shape, considering the storms that he has weathered, the personal as well as the political. In fact he is lucky to be here at all. Now a reformed chainsmoker, he was found to have lung cancer 12 years ago and went to Austria for life-saving surgery. Part of one lung was removed.

In that same year his wife Olga died, also of cancer. This was the woman whom he had married, against his mother's wishes, in 1964. She was also the muse who inspired him to write his Letters to Olga, about his beliefs and ideology, during his imprisonment between 1979 and 1984. Olga was a much-loved figure as the nation's First Lady during the 1990s, and Havel's own popularity took a serious knock when, the year after her death, he married the actress Dagmar Veskrnova. He later admitted that he had been having an affair with her for several years, but also credited her with having spotted the seriousness of his condition and urging him to seek treatment.

Dasha, as she is known, has remained a controversial presence. Havel wanted her to play a leading role in Leaving, but when the National Theatre in Prague vetoed the idea, he took the play to a rival theatre, the Divaldo Archa. As it turned out, Veskrnova didn't appear in the production in the spring as she was taken ill.

Havel has the same gruff charisma that endeared him to his fellow citizens when he was elected President. He gets tired; a loose cough rattles away in his chest; his assistant Sabina keeps a watchful eye. Just as his life straddled separate worlds, so is his manner an alliance of intellectual self-confidence and modest disbelief in his own significance. He came from a cultural and well-to-do family, studied economics at university, and was just 26 when his first play, The Garden Party, was staged and won international acclaim.

Nearly half a century later it is drama, not politics, that animates his often sombre features and opens a broad smile beneath his distinctive moustache. “But I have to say,” he explains, “the return to theatrical life wasn't as easy as I thought it would be. For 20 years I was a banned author, for 20 years I was a playwright President, so for 40 years I couldn't devote my life to the theatre. And it has changed meanwhile. Things are different. I'm different. There was a sort of media Schadenfreude expectation. I had political enemies and they were hastily awaiting my return [to the theatre] because they were expecting it would be a flop, and that I would be rolling in the mud. But it wasn't a flop. The reviews [of the Prague production] have been excellent.”

If he were still in his secondary career of statesman, what approach would he be advocating over Russia, still a great presence in the wings for the Czech Republic? The spectacle of Georgia must have stirred bitter memories.

“It's an old Russian problem - it was there before communism, during communism and after the collapse of communism. Russia doesn't quite know where it starts or finishes, because it is the largest country in the world and there is an apparent lack of trust in everything that concerns its neighbours, or in anything new. It is a typical Russian complex that has been brought out again by the Georgian war. I think the Western institutions like Nato and the EU should monitor it very well, and be vigilant, and say to Russia what they really mean, not pay lip service or remain silent over certain things.”

Sam Walters, the director of the Orange Tree Theatre, has been staging Havel's plays since the 1970s. The best ones, he says, such as Memorandum and Redevelopment, might have been expected to lose their power when the circumstances changed, but they have proved to be transcendent satires on human affairs. It was at that time that Havel and his fellow dissidents were drawing up their Charter 77 manifesto, prompted by the imprisonment of musicians from the Czech band called the Plastic People of the Universe. Havel may not see his life as a play, but the Czech-born Tom Stoppard saw quite enough drama in such episodes to incorporate them into his 2006 West End hit Rock'n'Roll.

Reluctant president perhaps, but the first true rock'n'roll premier. It was no affectation. Today his T-shirt has a bright logo for the Trutnov Open Air Music Festival. It was not just the Plastic People with whom he was friends, but Lou Reed, of the Velvet Underground, the iconoclastic US rocker Frank Zappa and those most assimilated of rebels the Rolling Stones. And all this began before that other rock enthusiast, Tony Blair, was even leader of the Opposition.

Leaving opens tomorrow at the Orange Tree, Richmond, TW9 (020-8940 3633; www.orangetreetheatre.co.uk)

Related Links