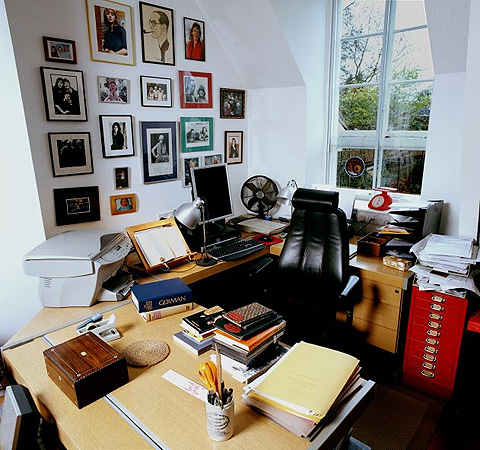

'Somerset Maugham said that writers should sit with their back to the window. I sit sideways on most of the time. Moderation in this, as in all things' ... Michael Frayn's writing room. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe/Guardian

'A play that shows how the divided selves of chancellor and spy echo the contradictions of the two Germanies' ... Roger Allam in Michael Blakemore's National Theatre production of Democracy. Photograph: Conrad Blakemore/National Theatre

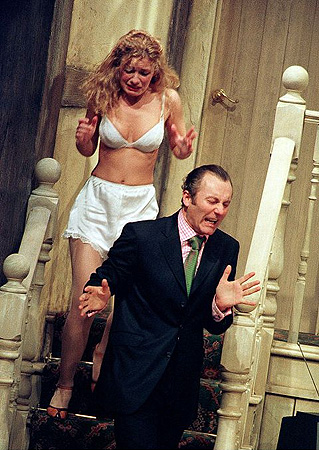

'Gloriously makes a bonfire of the genres and produces a kind of propulsive madness' ... Samantha Bond, Edward Petherbridge and Mark Addy in the West End revival of Donkeys' Years. Photograph: Tristram Kenton/Guardian

Lyttelton, London

Lyttelton, London

Morality play... Roger Allam in Afterlife at the National Theatre. Photograph: Tristram Kenton

Morality play... Roger Allam in Afterlife at the National Theatre. Photograph: Tristram Kenton Theatre itself has been a key metaphor in Michael Frayn's work - from the farcical Noises Off to the philosophical Look Look. Now Frayn turns his attention to the legendary Austrian director Max Reinhardt, whose production of Everyman outlives its creator by playing annually in Salzburg's Domplatz. But, while Frayn's play ripples with invention and is beautifully staged by Michael Blakemore, it is difficult to discover universal resonance in Reinhardt's career.

Frayn tackles the problem head-on by using the framework of Everyman, a medieval morality play adapted by Hugo von Hofmannsthal, to explore Reinhardt's life. We first see the Jewish director in 1920 persuading Salzburg's Catholic archbishop of the need for a public spectacle about the human capacity for change. And Frayn draws constant parallels between the play's hero and its director. Reinhardt, like Everyman, is an acquisitive materialist, and just as the symbolic figure of Death claims Everyman, so Reinhardt's career is destroyed by the 1938 Anschluss.

You can see what Frayn is driving at: to suggest that art offers an equivalent to the religious afterlife and that the survival of Reinhardt's visionary idea of theatre as a waking dream matches Everyman's ultimate redemption. But, in practice, it does not quite work, because Frayn seems straitjacketed by the morality play format. He focuses too much on Reinhardt's latter-day reputation as a creator of baroque spectacles, ignoring his early work, and also implies that Reinhardt's American exile was one of impoverished despair: in reality, he went on working to the last. In seeking to transform Reinhardt into Everyman, Frayn is forced to be factually selective.

There remain, as you would expect in Frayn, delicious ironies such as Reinhardt's simultaneous attempt to play God and appeal to the common man. Blakemore's superbly marshalled production also contains some exquisite moments: best of all is one in which Reinhardt directs his footmen and maids in a mealtime minuet. This also allows the excellent Roger Allam to demonstrate that Reinhardt was most vibrantly alive when confronted by practical staging problems, but remained a shadowy, elusive figure in his private life. Peter Forbes as his long-suffering business manager and David Schofield as his demonic opponent, who turns into a Nazi Gauleiter, are equally impressive. But, while the play draws attention to a neglected theatrical master, it leaves you feeling that Frayn has been circumscribed rather than liberated by his chosen morality-play structure.

![]() Lyttelton, London

Lyttelton, London

No comments:

Post a Comment